The stones left unturned in the Sam Bankman-Fried trial

From billions of mysterious Tethers to the apparent identity theft of Thai sex workers, many questions remain about what happened at Bankman-Fried's crypto empire.

Now that Sam Bankman-Fried has been convicted in one of the largest financial fraud cases in history, the crypto industry would like people to please hurry up and move on. The trial is over, and it's just so dang inconvenient that Bankman-Fried so publicly ruined the general reputation of an industry rife with scams and frauds by making it seem as though it is an industry rife with scams and frauds.

However, this ignores the web of malfeasance that surrounded his companies, and much more apparent wrongdoing perpetrated not only by its executives, but by others in the industry. Bankman-Fried's criminal trial was focused on securing a fraud conviction, not untangling the knot of curious threads that, if pulled, could unravel dozens of different fraud-sweaters.1

Prosecutors painted a picture for the jury that clearly outlined criminal activity that supported his wire fraud, conspiracy, and money laundering charges without getting too deep into the weeds or chasing tangents that might only confuse.

But regularly throughout the trial, prosecutors, witnesses, or even Bankman-Fried's own defense team made brief mention of topics that sounded ripe for deeper investigation, only to move on and never mention them again. While some of these topics might resurface in Bankman-Fried's next criminal trial (should it happen at all), as a part of adversary proceedings in the FTX bankruptcy case, or in separate legal cases, the limits of investigative resources and jurisdictional cooperation may indefinitely condemn the rest to remain unsolved mysteries.

Tether

The elephant in the room throughout the trial was Tether. Tether is a shadowy stablecoin provider that powers truly massive portions of the cryptocurrency industry. The organization has been fined and banned from doing business in New York after the Office of the Attorney General discovered they were lying about the coin's backing, and though the company has spent years promising to publish audits of the more than $80 billion Tethers (abbreviated to USDT) in circulation, they have produced none.

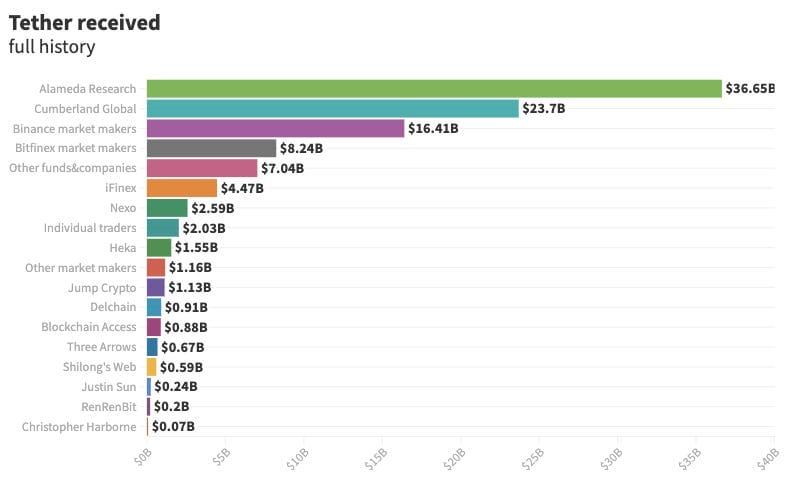

Besides exchanges, Alameda Research was Tether's largest customer. We know that the company received around 40 billion of the tokens: almost half of the token's current circulating supply, and 20% of the tokens ever issued by the company.a2 What we don't know is why, or with what money they purchased such a massive quantity of tokens.

Although cryptocurrency companies routinely purchase USDT from Tether with dollars and then redeem USDT for dollars in the opposite direction, Alameda Research appears to have only ever redeemed a small portion (around $4 billion) of the USDT they bought.

In the past, Alameda has claimed they used USDT to profit from arbitrage opportunities3 (that is, obtaining USDT from Tether at $1 and selling it on the markets at above $1 to people who don't have the institutional access required to purchase USDT directly). However, whether there was truly demand for $40 billion of the stablecoin seems questionable at best. Exchanges like FTX also regularly facilitate the exchange of dollars for stablecoins by their customers, but again, not to the tune of $40 billion.

Some, like Jacob Silverman in The Nation, have suggested that Alameda and FTX may have in fact been using the tokens to enable money laundering and capital flight (particularly out of China, which has strict capital controls). Others, like David Z. Morris, have questioned whether Alameda ever actually sent Tether the roughly $40 billion in cash that would be needed to properly back the tokens, or if the tokens could have been minted with no backing — which would mean that a substantial portion of USDT on the market today could never be redeemed if it ever came down to it.

Further reading: The Nation, Protos, Bloomberg (with further commentary from David S. H. Rosenthal), David Z. Morris.

Moonstone Bank

Sometimes lost among all the other shady business surrounding FTX is that time that Alameda Research went out and bought a bank. Until 2020, Farmington State Bank was just a tiny bank in a rural town in Washington state.

Then, it was snapped up by a company called FBH, which is chaired by Jean Chalopin (also chairman of the Bahamas-based Deltec Bank and Trust, which has been a major bank for both Alameda Research and for Tether). Under new ownership, Farmington State Bank applied for Federal Reserve approval and began taking on cryptocurrency clients (despite promises to state regulators and the Fed that it would not do so). In June 2021, the bank became a part of the Federal Reserve System.

In March 2022, Alameda Research sent $11.5 million to the bank, which only days prior had adopted the name "Moonstone" as a reference to the two industries it hoped to pivot to serve: cryptocurrency ("to the moon") and cannabis ("getting stoned").

As yet unanswered: why did Alameda Research sink $11.5 million — over twice the bank's net worth — into this once tiny bank? Was it an effort to obtain uninterruptible access to the US banking system for cryptocurrency companies?

After FTX and Alameda's collapse, the bank was forced to shut down for reneging on its promises to regulators. But the questions of how the Bahamas-based Jean Chalopin, Deltec, and Alameda Research managed to gain control of a US bank and achieve Federal Reserve approval remain open, as does the question of what they hoped to achieve with it under their control.

Further reading: Protos, Crypto Critics' Corner.

The MobileCoin theft

As you may have noticed if you read my article for the New York Times last week, I've been fascinated by the new details we learned during Bankman-Fried's trial about an exploit of FTX by a trader who took large positions in MobileCoin (MOB) and BTMX tokens. Although the public learned of the 2021 theft shortly after FTX's collapse the following year, thanks to reporting from the Financial Times that cited people with knowledge of the matter, the trial gave us more details.

We learned that the total loss to FTX was around $800 million (though Bankman-Fried refused to admit during his testimony that there had been any loss at all). We learned that Bankman-Fried had been concerned about just liquidating the account when other executives raised concerns that it was attempting to exploit FTX, "because they were otherwise a valuable customer". And we learned, thanks to questioning from his very own defense team for some reason, that Bankman-Fried himself "overrode FTX's standard risk procedures there and personally took responsibility for that account".b (This, by the way, somewhat contradicted his testimony during cross-examination the previous day, when he claimed that the automatic liquidation engine "didn't shut it [the position] down as quickly as I would have wanted it to".c)

What we haven't learned is who this customer was, or why they were so valuable that Bankman-Fried thought it was worthwhile to avoid liquidating them even when facing a threat of an exploit that could — and did — cost the company almost its entire annual revenue for that year. There has also been no evidence that FTX ever tried to recoup the funds via legal action against the customer, whose identity should presumably have been known to FTX as a part of their standard know-your-customer process (which Bankman-Fried also described in his testimonyd). Why not?

The mid-collapse hack

Only hours after FTX declared bankruptcy, crypto priced at hundreds of million dollars (later estimated at around $477 million) was stolen [W3IGG]. Some of those funds were ultimately frozen by stablecoin providers, and the thief lost more to fees as they exchanged centrally-controlled stablecoins for unfreezeable tokens and then laundered them, but the thief still found themselves with a massive pile of crypto, and FTX's financial condition (and thus that of its creditors) was worsened by the nearly half a billion dollar loss. In an ironic twist, one of the services used to launder the stolen funds in attempts to prevent them from being recovered by law enforcement was RenBridge — a cryptocurrency bridge owned by Alameda Research.

After the early race to convert and launder the funds, most of the assets remained dormant… that is, until the days before Bankman-Fried's criminal trial began, when the funds went on the move again as the thief attempted to cash out.

Not long after the theft, Bankman-Fried claimed in a recorded phone call with Tiffany Fong that he had "narrowed it down to like eight people", using the subject as an opportunity to express his frustration that the new team in charge of his company in bankruptcy had so unfairly shut off his access to company data as he was suspected of massive fraud. He further stated that he believed the hacker was either an ex-employee or that someone had installed malware on a former employee's computer.

However, such claims have not been corroborated by anyone else, and any investigations of the theft as yet have occurred behind closed doors.

The frozen funds and bribe of Chinese officials

Trial testimony featured Alameda Research CEO Caroline Ellison and others talking about statements like "-150m from the thing?", which she stated was coded language to avoid putting the existence of a multimillion dollar bribe to foreign officials in writing.

After the Chinese government requested an unnamed cryptocurrency firm freeze around $1 billion of funds belonging to Alameda Research as part of a money laundering investigation (which Alameda has claimed was not targeted at them), FTX and Alameda executives tried several creative routes to getting their hands on the money. When lawyers didn't work, the executives tried setting up accounts using the stolen identities of Thai prostitutes, a claim that I think everyone in the courtroom was disappointed not to hear prosecutors ask more about.

Finally, the executives decided to send a $150 million bribe to the officials, who subsequently released the frozen assets.

The good news here is that, if Bankman-Fried's second trial in March goes forward, we may hear more about this particular saga. One of the charges he's set to face is conspiracy to violate the anti-bribery provisions of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

The donations

The topic of Bankman-Fried's massive donations flew mostly under the radar during his trial, in no small part because prosecutors dropped a specific charge pertaining to that activity and instead had to lump the behavior in with the wire fraud charge. As a result, they were somewhat limited in how detailed they were allowed to get in describing his behavior, so as not to suggest he was charged with a campaign finance crime. Nishad Singh, who pleaded guilty to a campaign finance charge, did describe some of the malfeasance in that arena, but it was fairly brief. Ryan Salame, the other exec to plead to a campaign finance charge, is not cooperating with prosecutors and did not testify.

Many questions remain when it comes to the huge political and charitable donations made by Bankman-Fried, which were often sent via a mix of his companies and their executives in order to conceal their true origins.

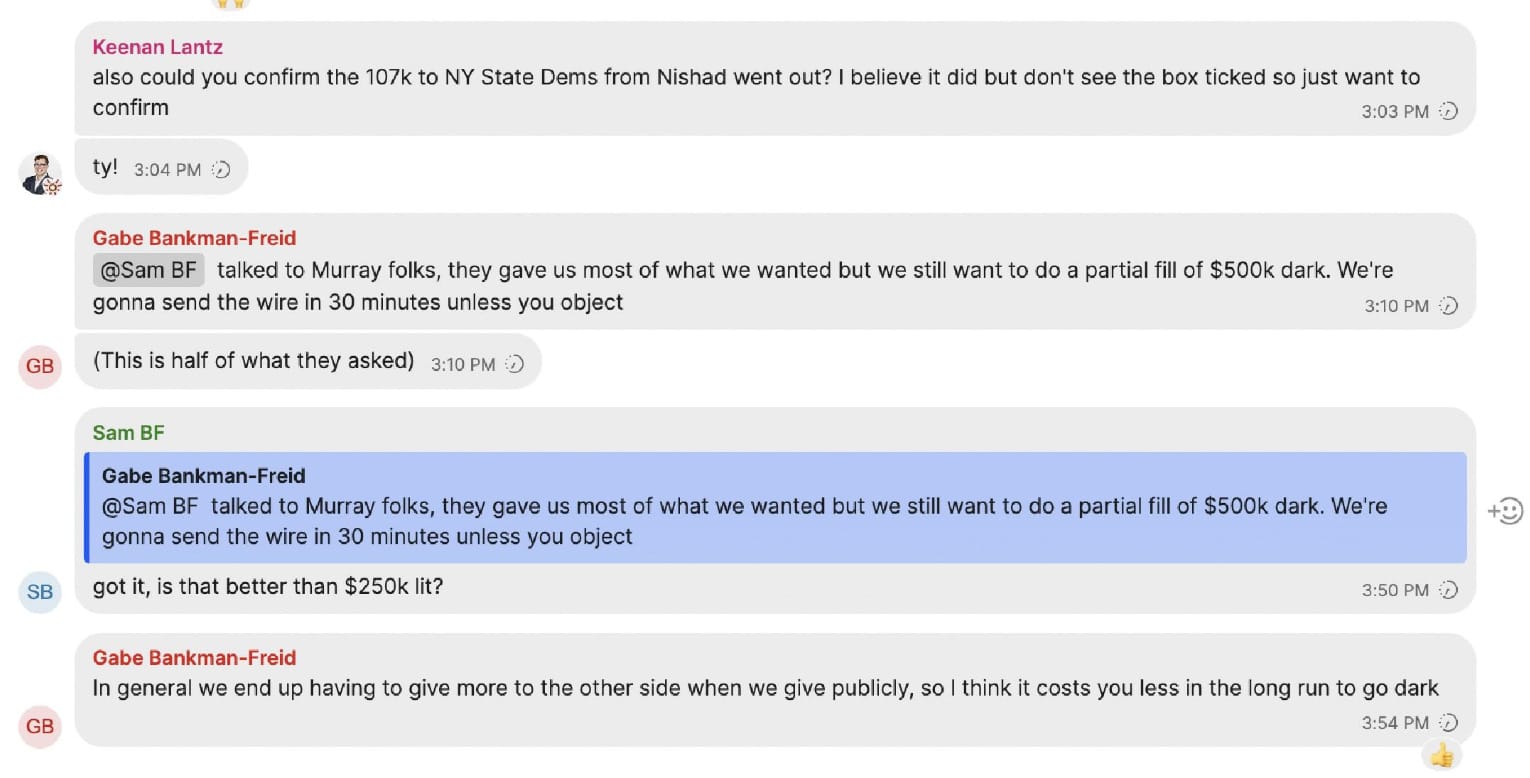

For one, it seems like Bankman-Fried, Singh, and Salame were far from the only people involved: group chats published in government exhibits show conversations with Bankman-Fried's brother Gabe and various others at Gabe's Guarding Against Pandemics (GAP) organization in which they appear to be well aware of the illegal financial maneuvers. Gabe Bankman-Fried stepped down from the organization shortly after FTX's collapse, claiming he "didn't want to be a distraction". But Keenan Lantz, the interim executive director who stepped up to replace him, himself featured heavily in chats produced during the trial where "dark" and straw donations were being openly discussed.

Shortly after Bankman-Fried's conviction, GAP announced it was shutting its doors.

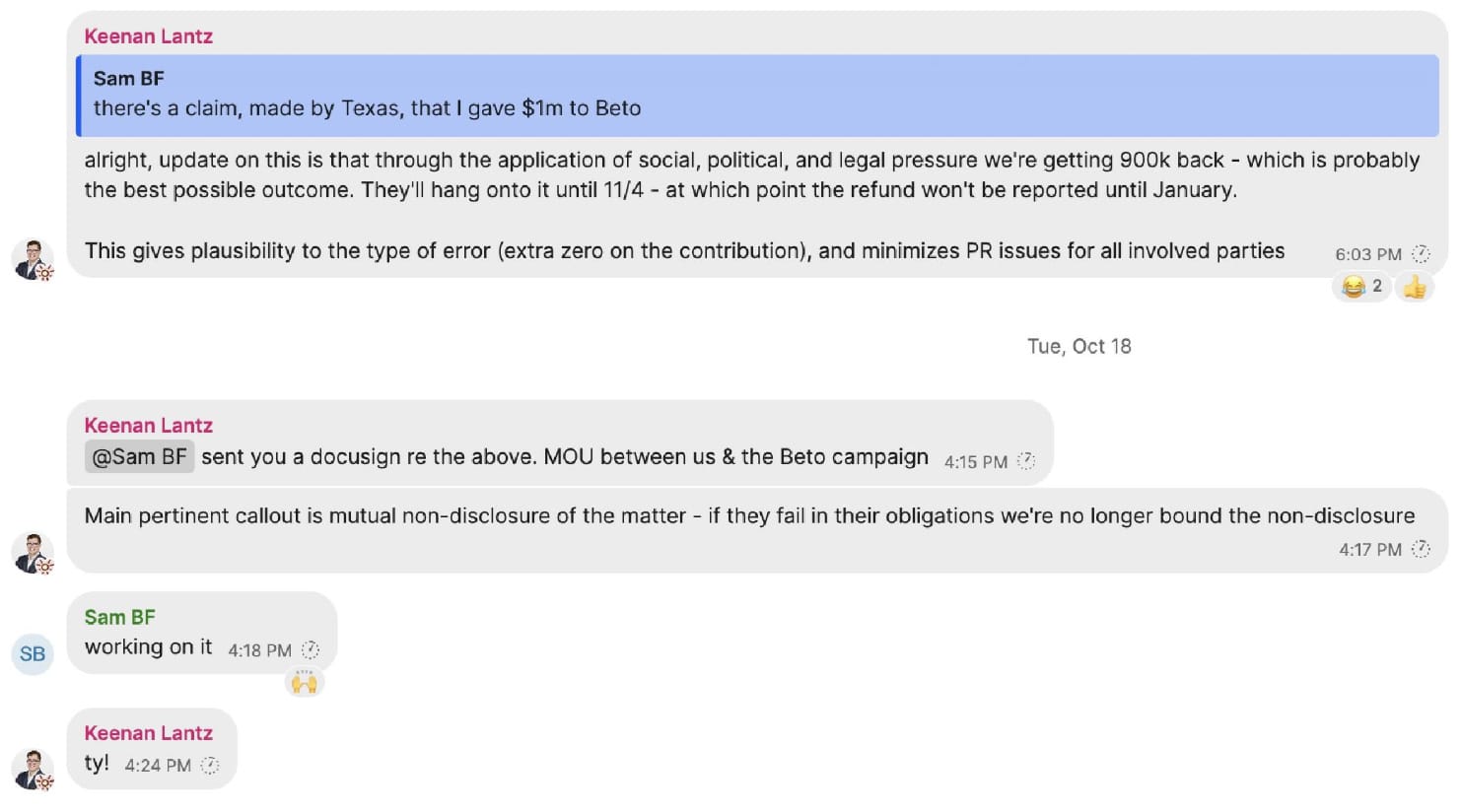

There are also questions about the recipients of those donations. A Signal discussion between Bankman-Fried and GAP's Keenan Lantz of a $1 million donation to Beto O'Rourke's campaign suggested that Bankman-Fried might have demanded it back after it made the news in Texas:

This seems to contradict the O'Rourke campaign's public telling of the story shortly after FTX's collapse, which is that they received the donation by surprise and returned it because it was unsolicited.

Another conversation between political consultant Michael Sadowsky and Nishad Singh raises questions about whether Congresswoman Becca Balint (D-VT) knew that straw donations made via a "passthrough" donation to the LGBT Victory Fund PAC were in fact coming from FTX, taking the winding route via the LGBT fund to avoid the appearance that she was accepting super PAC money after being pressured by an opponent to denounce such a thing at a debate. (Balint has denied having such knowledge of this donation and where it came from.)

Chats also referred to a $107,000 donation to the New York State Democratic Committee that was originally to come from Sam Bankman-Fried until "we were asked to update this to a 107k contribution from Nishad Singh" (according to Lantz).

One back-and-forth referred to sending "$500k dark" to Senator Patty Murray (D-WA), with Gabe Bankman-Fried describing it as "half of what they asked".

Another conversation sought a correction in a misreported story that erroneously attributed a $500,000 donation by Singh to the Democratic Party of Oregon PAC as having come from Prime Trust, an unaffiliated cryptocurrency custodian that is somewhat ironically now dealing with its own woes. Amusingly, at the time — only days before FTX's fall — the correction itself sparked concerns about straw donations from Oregon Live.

The prevalence of dark donations and attempts to mask funds by sending them through various political groups is no secret to anyone who's even vaguely familiar with the American political system, but the openness with which these groups seemed to discuss such activities with the eventual recipients of the donations sure seems like it would be cause for concern among those tasked with scrutinizing election fairness and compliance with campaign finance requirements.

Paper bitcoin

During November and December 2022, during the media tour in which Bankman-Fried seemed determined to publicly admit to as many crimes as possible, a participant in a group interview on Twitter Spaces asked Bankman-Fried to answer a simple question: when a trader thought they were sending dollars to FTX to buy Bitcoin, was that Bitcoin ever actually purchased or was the company just holding on to the dollars to use for their own purposes? In other words, was FTX issuing "paper bitcoin" or "notional bitcoin" (or other tokens) to traders, representing tokens that did not actually exist?

Bankman-Fried replied: "I believe that was a part of the story."

Although it's pretty clear by now that FTX was experimenting with its own, clearly fraudulent form of "fractional reserves" by failing to keep on hand the total value of assets its spot trading customers believed they held, not much time has been spent discussing the types of assets it failed to keep on hand.

FTX failing to keep sufficient US dollar reserves is not going to affect the value of the US dollar, but FTX failing to keep sufficient reserves of Bitcoin, Ethereum, or whichever other token they supported could substantially affect these thinly-traded markets.

Tokenized stocks

Similar allegations around backing have come out against FTX's tokenized stocks offering, which allowed customers to purchase synthetic versions of shares in public companies. Although FTX claimed that all tokenized stocks were backed by real shares, and could be redeemed for them through a partnership with a German investment firm called CM-Equity AG,4 that partnership ended in late 2021 — raising questions as to whether those shares were properly backed from that point on.5

Besides the backing questions, there are also regulatory questions. Binance backed down from tokenized stock offerings in mid-2021 after German regulators warned them that its version of the product likely violated securities laws.6 FTX's offering was substantially similar.

The VC reciprocity

Sequoia Capital invested around $225 million into FTX in several of its funding rounds. FTX and Alameda together invested around $200 million into Sequoia.

Alameda Research invested $25 million into a fund managed by Paradigm Capital. Paradigm Capital invested $278 million into FTX.

This is not the end of the list of circular investments, where money traveled from Bankman-Fried's companies into VC funds only to loop back to FTX, or vice versa. Bankman-Fried invested in funds run by UVM Signum,7 Altimeter Capital Management, and Multicoin Capital,8 and those funds invested in FTX. Altogether, Bankman-Fried's companies poured more than half a billion dollars into various VC firms, but some of it came right back.

What was the purpose of this money-shuffling? And, both Sequoia and Paradigm have written their investments off to zero, but what happened to the funds that went in the other direction?

The auditors

FTX boasted of its audited financial statements, which were produced by the likes of Armanino and Prager Metis. However, we've since heard in great detail about the absolute clusterfuck of napkin math, QuickBooks, and eight-tabbed "alternative" balance sheet spreadsheets that was FTX and Alameda's gesture at accounting.

How did auditors not catch this? Beyond just making sure numbers in a spreadsheet add up, auditors are supposed to also identify possible organizational and managerial deficiencies that could introduce risk to a company. The FTX "organization" and "management", if it could even be called that, was nothing but deficiency and risk. Bankman-Fried biographer Michael Lewis spoke of having to try to cobble together a list of employees and their job titles from the company therapist Professional Coach,e for god's sake!

The missing executives

If you've been reading my work for a while now, you'll know of my "conspicuously missing executives" list. It's gradually dwindled as people like Ryan Salame (former CEO of FTX's Bahamian entity) belatedly reached plea deals, or as executives like Ramnik Arora (leader of the companies' venture investing) were placed on the prosecution's list of possible witnesses.f Two names that have remained are Sam Trabucco and Daniel Friedberg.

Last we heard from Trabucco, he was sailing off into the sunset on Soak My Deck, a 52-foot yacht purchased for him by the company. Though he was described as a star trader by both Bankman-Fried and Ellison, both of them also claimed that he more or less checked out of the company when he was appointed co-CEO in mid-2021, and stopped showing up to the office or participating meaningfully in discussions . However, he only resigned in August 2022, though he said he would be "stay[ing] on as an advisor". His most recent tweet was on November 8, 2022, the day of the FTX collapse: "Much love to everyone -- I'm sure the past few days have been dark for many and I hope the road ahead is brighter." His name came up a few times in the trial, and it seems hard to believe that he could have been co-CEO — even if largely in name only — through August 2022 without knowing where his company was magically obtaining billions of dollars in funds. Even still, no charges against him have been published, and it's not clear if he's cooperated with prosecutors.

Daniel Friedberg is also conspicuously missing, though it does appear that he has cooperated at least somewhat with investigators. A Reuters report in January 2023 suggests he began speaking to investigators as soon as November 22, 2022 — only two weeks after the company's bankruptcy. However, although prosecutors suggested he's a shady character who does shady things (they suggested he was not a "respectable attorney" who was competently trying to keep FTX on the right side of the law, and even tried to question Bankman-Fried on whether he was aware that Friedberg had "used illegal narcotics" with employees), Friedberg also hasn't been publicly charged. Nor has he been asked to account for his apparent pattern of providing legal advice to companies involved in massive frauds — first at the online poker casino Ultimate Bet, then at FTX.

The parents

Bankman-Fried's parents offer a dilemma to observers of the FTX trial, who must decide where they fall on the spectrum from "naive parents devastated to learn that their son was a fraudster who is now facing decades in prison" to "fully aware that their son was engaged in criminal fraud because they too were engaged in it".

An adversary case filed by the FTX bankruptcy team only weeks before Bankman-Fried's trial began paints them as much closer to the "criminal participant" side of the spectrum, seeking to recoup illegitimate transfers to them from the companies, including a $10 million "loan" and other benefits. The suit suggests that Barbara Fried instructed FTX employees to make straw donations to obscure where political and charitable donations were coming from. It also shows Joseph Bankman as heavily involved in FTX's day-to-day operations, providing legal and financial input, and ultimately requesting a $1 million salary from the company. Descriptions of Signal group chats published into evidence during his son's trial also have him listed as a participant in several, including the "small group chat" that functioned as a sort of war room as Bankman-Fried and his executive team desperately tried to stop the FTX collapse as it was underway.

The true extent of his parents' involvement may never come out. They have vociferously denied the claims by the FTX debtor team, and I doubt criminal prosecutors are going to pursue a case against them unless they were pivotally involved, given the convictions prosecutors have already secured against their son and FTX's other top leadership. Going after the parents, who are around 70 years old, whose reputations, careers, and finances have already been destroyed, and who have continued to be painted as somewhat pitiable figures in the media even after the adversary case was published, could be seen as a purely vindictive move with little real benefit.

Criminal cases are intended to explore the facts around an alleged crime, at least to the degree necessary to convince a jury beyond a reasonable doubt of the perpetrator's guilt. The goal in Bankman-Fried's case, sadly for me, was never to spend months trying to satisfy the endless curiosity of crypto watchers seeking to understand and dismantle the systemic malfeasance in the cryptocurrency world.

Although this is unsatisfying, the case has nevertheless provided much more information than was previously publicly known, which civil litigators, journalists, researchers, and others will surely continue to pore through for the coming months and years. Hopefully it will at least offer a push towards turning over more of those stones it left unturned.

Social image: "Cairns in Puerto de la Cruz. Tenerife. Spain eue53" by Lmbuga (Luis Miguel Bugallo Sánchez), CC BY-SA 4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons)

Footnotes

Tether mints new tokens when a client buys them from the company, and burns tokens when a client returns the tokens to Tether to redeem them for dollars. As such, the number of tokens ever issued exceeds its current circulating supply. ↩

Bankman-Fried testimony, October 31, 2023. ↩

Bankman-Fried testimony, October 30, 2023. ↩

Bankman-Fried testimony, October 27, 2023. ↩

George Lerner was a licensed psychiatrist in the US, but he wasn't licensed to practice in The Bahamas, so he took the title "Senior Professional Coach". Whatever he was, he sure didn't sound like a therapist: according to Lewis's telling, "What [Bankman-Fried] liked about George was that George simply took him as he was—and actually didn't seem all that interested in engaging in pointless conversations about his feelings. Sam had long since decided that any discussions about his inner life, and its consequences for others, were futile. 'The social stuff was basically unsolvable,' he said. He didn't need a therapist to deal with his problems—though he did need someone who could prescribe his medications." (Going Infinite, p. 139 digital edition) ↩

Arora ultimately wasn't called to testify. ↩

References

A fraudigan, if you will. (All credit to Popehat for that one). ↩

"Bankman-Fried Trial Renews Conjecture About Alameda's Tether Ties", Bloomberg. ↩

As former Alameda Research co-CEO Sam Trabucco once suggested on Twitter. ↩

"What to Know About FTX's GME Tokenized Shares", The Street. ↩

"Binance ditches 'stock tokens' as global crackdown widens", Reuters. ↩

"FTX boss invested in Paradigm fund that backed his crypto exchange", Financial Times. ↩

"FTX's Bankman-Fried Quietly Invested More than $500 Million in Sequoia and Other VCs", The Information. ↩