“But the SEC let us go public” and other flawed arguments in Coinbase's defense

Coinbase is trotting out its usual flawed arguments now that it's facing a lawsuit from the SEC, and more pushback is needed.

The day after filing their lawsuit against Binance, the Securities and Exchange Commission sued Coinbase.

For more on the Binance lawsuit, see my previous special edition:

For some detail on the two cases, an explanation of how they're similar and where they differ, and a discussion of what they're likely to mean for the crypto industry in the United States, you may enjoy my recent article in Rolling Stone: "The Feds Are Coming for Crypto. Can It Survive?"

There are enough explainers and overviews of the Coinbase case already (such as this detailed one by David Gerard and Amy Castor) that I won't duplicate those efforts. However, I would like to dig a little bit into some of Coinbase's public relations — and likely legal — strategy when it comes to their battle against the SEC.

Coinbase has established a reputation in the United States as the "legit" crypto exchange, and was once known for its conservative approach to listing assets that could be traded using their platform. They were founded in the US in 2012, they hold a BitLicense from the New York Department of Financial Services, and they went public on the Nasdaq stock exchange in April 2021. They present themselves as very by-the-book, and brag about their eager cooperation and regular meetings with US regulators.

However, Coinbase has in the past few years taken an aggressive stance against the SEC and its Chairman Gary Gensler, and the two groups have butted heads with increasing frequency. In July 2022, the firm filed a petition for rulemaking, asking the SEC to write and adopt bespoke rules for the cryptocurrency industry. According to Coinbase, the technological innovation behind crypto marked "a paradigm shift from existing market practices, rendering many of the Commission rules that govern the offer, sale, trading, custody, and clearing of traditional assets both incomplete and unsuitable for securities in this market". They argue that the 1930s-era acts that still underpin securities law in the US are insufficient to regulate crypto. In March 2023, Coinbase filed an amicus brief in a case against a former Coinbase product manager and his accomplices, in which they took issue with assertions by the SEC that several cryptocurrency tokens listed on Coinbase were securities. In April, Coinbase filed a petition for a writ of mandamus, urging the court to compel the SEC to respond to its petition filed less than a year prior, and claiming that the SEC had already made a decision to reject it but had not published that decision.

Coinbase and its executives accuse the SEC of "regulating by enforcement", and not providing sufficient "regulatory clarity" for the industry. Gensler, on the other hand, has said: "Crypto markets suffer from a lack of regulatory compliance. It's not a lack of regulatory clarity." Gurbir S. Grewal, director of the SEC's Division of Enforcement, adds: "You simply can't ignore the rules because you don't like them or because you'd prefer different ones." Gensler firmly maintains that the vast majority of crypto assets are securities, with the exception of Bitcoin, and therefore that the unregistered exchanges, broker-dealers, and clearing agencies operating in the US crypto industry are violating the law.

Now that the formal lawsuit has been filed against Coinbase, a lot of the arguments they've come up with over the last few years are being regurgitated in the media, often with too little pushback.

"Securities laws written in the 1930s can't apply to crypto"

It is often difficult to determine what a jurist was thinking when they drafted a given piece of law, but I think it is reasonable to assume that none of the authors who drafted these securities statutes from the 1930's, or the subsequent Supreme Court tests interpreting those statutes, did so while thinking of a day when a decentralized, cryptographically-based, automated financial instrument would be adopted en masse by millions of people in the United States and around the world.

Put simply — when these authors were writing rules to regulate square pegs, they did not account for how those rules would impact the unpredictable round holes of the future.

There is nothing about the crypto securities markets that suggests that investors and issuers are less deserving of the protections of our securities laws.

Congress could have said in 1933 or in 1934 that the securities laws applied only to stocks and bonds.

"Congress's purpose in enacting the securities laws was to regulate investments, in whatever form they are made and by whatever name they are called." This is not just a talking point. This is the law of the land, as Justice Thurgood Marshall wrote in the Supreme Court's famous Reves decision.

Securities laws were not written for a specific type of asset or technology, but were rather created to regulate the investment that was involved. They apply to everything from classic stocks to citrus grove offerings (1946) to whisky warehouse receipts (1973) to beaver caretaking contracts (1967), without any of the latter three things being mentioned in the text of the law. It's not likely the 1930s jurists were thinking about beavers while drafting, either.

"But the SEC let us go public"

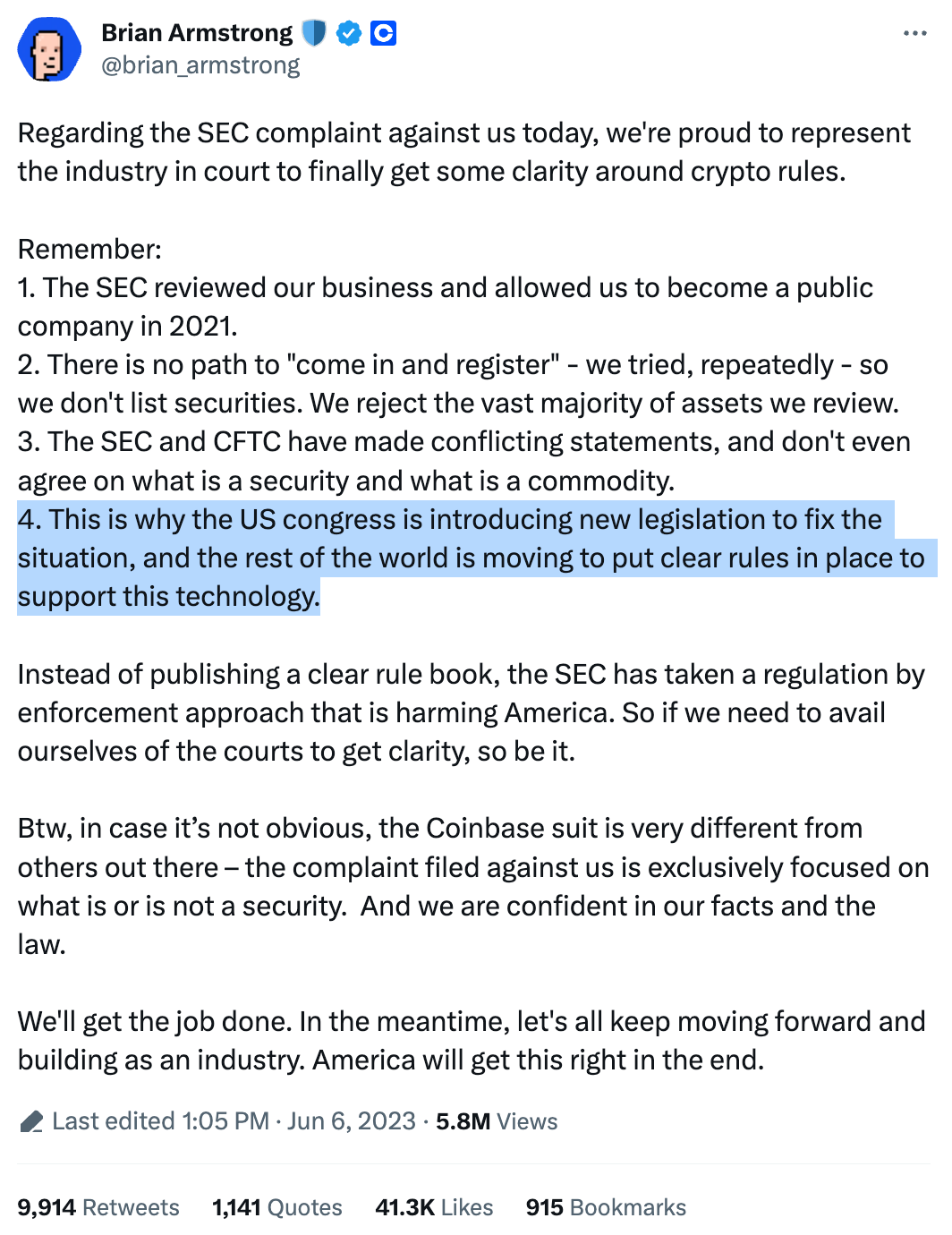

Responding to the recent lawsuit against his company, Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong tweeted: "Remember: The SEC reviewed our business and allowed us to become a public company in 2021." Chief legal officer Paul Grewal has made similar statements. Their argument is that if the SEC thought they were illegally offering securities, they should never have allowed them to go public. And perhaps they shouldn't have, argued Lionel Laurent in a recent opinion column for Bloomberg. But the SEC's 2021 declaration that Coinbase's registration statement was "effective" has very little bearing on their recent complaint against the company.

When a company goes public, the SEC's role is to review their registration statements and ensure they comply with disclosure requirements. That's it. In fact, the SEC states at every possible opportunity when describing the process that the agency "does not evaluate the merits of the securities offering".

On the fourth page of Coinbase's lengthy S-1 form from when they filed to go public, printed in bold type, Coinbase confirms that very thing:

Neither the Securities and Exchange Commission nor any other regulatory body has approved or disapproved of these securities or passed upon the accuracy or adequacy of this prospectus. Any representation to the contrary is a criminal offense.

That last bit should make Armstrong and Grewal a bit nervous, I'd think, though I don't know how often the SEC actually brings complaints regarding that clause.

If we think about this for more than two seconds, and broaden our view beyond Coinbase, it makes common sense. Look at a list of the five most recent IPOs and their businesses:

- Atmus Filtration Technologies: filtration products for on-highway commercial vehicles and off-highway agriculture, construction, mining and power generation vehicles and equipment

- CaliberCos: asset management

- Strong Global Entertainment: movie theater screens and projection systems

- Acelyrin: pharmaceuticals for immunological diseases

- Kenvue: consumer health company that manufactures brands from Band-Aids to Listerine to Neutrogena

If the SEC was in the business of making merit-based judgments on companies before they went public, they would need to somehow have expertise in everything from industrial filtration to financial management to projection technology to biotech to the manufacture of skincare products, bandages, and mouthwash. It's simply not feasible, much less desirable.

Coinbase also writes in great detail in the S-1 about the risk that the SEC might bring a lawsuit exactly like the one they just have:

[W]e could be subject to legal or regulatory action in the event the SEC, a foreign regulatory authority, or a court were to determine that a supported crypto asset currently offered, sold, or traded on our platform is a "security" under applicable laws… [W]e could be subject to judicial or administrative sanctions for failing to offer or sell the crypto asset in compliance with the registration requirements, or for acting as a broker, dealer, or national securities exchange without appropriate registration.

[T]here is regulatory uncertainty regarding the status of our staking activities under the U.S. federal securities laws.

The two possible explanations here are that neither Armstrong nor Grewal (the latter a highly experienced lawyer and former magistrate judge) understand the law or are familiar with Coinbase's own SEC filings, or that they're knowingly misrepresenting it as a part of their public relations strategy.

"There is no path to compliance"

I'll give it to them, they might be right on this one. Coinbase thinks this is an issue with the securities laws. The SEC thinks this is an issue with Coinbase.

If a company went to the FDA and said "hello, we'd like to start selling heroin to the public for recreational use", and the FDA said "no, you can't do that", the company could loudly complain that the FDA was not giving them a path to compliance. People would probably laugh at them.

The company could decide the FDA was wrong, demand that they and/or Congress write new rules to allow for this innovative new heroin business that would bolster American capital markets, and decide that in the meantime they were going to sell heroin anyway. People might not be terribly sympathetic when it didn't end well for them.

Coinbase, as with most crypto platforms, has decided it wants to simultaneously operate as an exchange, broker-dealer, and clearing agency. These three functions — bringing together securities orders for buyers and sellers, trading securities on behalf of others, and intermediating trades — are typically required to be separate due to conflicts of interest that emerge when one entity controls all of them. Coinbase would need to fundamentally change its business model in order to separate these functions, and thus far seems unwilling to do so. "[Crypto intermediary compliance is] not just a matter of 'paying lip service to [the] desire to comply with applicable laws' or seeking a bunch of meetings with the SEC during which you're unwilling to make the changes needed to comply with the securities laws," said Gensler in a speech a few days ago.

And registering as even one of these types of businesses involves a disclosure, inspection, and auditing process more akin to what one might expect at a proctologist's office. It's not an easy process for most above-board operations, much less a crypto company.

Less than a week after the lawsuit was filed, we can't know much about Coinbase's likely legal strategy. But based on their past actions, my guess is that it's going to involve a lot of PR stunts and headline-grabbing gambits involving these very same arguments. And from Armstrong's tweet, I can infer that Coinbase seems to be hoping for a deus ex machina in the form of Congressional intervention:

Congress has been far from united on the crypto issue thus far, particularly in the wake of the FTX collapse, and the various drafts of legislation that have been proposed have largely been dead on arrival. But Coinbase has put a significant amount of time, effort, and money into lobbying: in 2022, they spent $3.4 million lobbying the crypto industry (on top of Binance's $1.1 million spent lobbying in the US, all coming together to amount to around $11.9 million in lobbying efforts from the industry that year).

The lobbying seems to have made an impact. When the SEC filed its cases against Binance and Coinbase, some Congresspeople sprung into action, but not to aid the agency in regulating an industry marred by a year of collapses and harm to US customers. Today, Representatives Warren Davidson (R-OH) and Tom Emmer (R-MN) introduced the "SEC Stabilization Act" with one primary goal: to fire the "tyrannical" SEC Chairman Gary Gensler.