Coinbase appears to have violated campaign finance laws with a $25 million super PAC donation

Actively involved in contract negotiations with a federal government agency, Coinbase was likely prohibited from making its $25 million contribution to the Fairshake cryptocurrency-focused super PAC in May 2024.

With $45.5 million in corporate contributions, American cryptocurrency exchange Coinbase is the largest donor to Fairshake: a newly minted super PAC focused solely on installing political candidates who will be friendly to the cryptocurrency industry, and ousting those with a history of pushing for stronger regulations and consumer protections when it comes to an industry that has long been a regulatory “Wild West”.

Coinbase’s donations to the super PAC came in three installments: $5 million contributed in November 2023,1 $15.5 million in December 2023,2 and another infusion of $25 million on May 30, 2024.3a Coinbase announced the latter contribution a few days later on their blog on June 3 in a post titled “How to get regulatory clarity for crypto”. They repeated dubious claims about the number of Americans who own cryptocurrency and the “grassroots” nature of their Stand With Crypto advocacy group, and described the spending as an attempt to “send a clear message to political candidates that it is bad politics to be anti-crypto”.

This $25 million contribution, however, appears to be in violation of federal campaign finance laws that prohibit contributions from current or prospective federal government contractors. This would be by far the largest known illegal campaign contribution by a federal contractor.

The contract

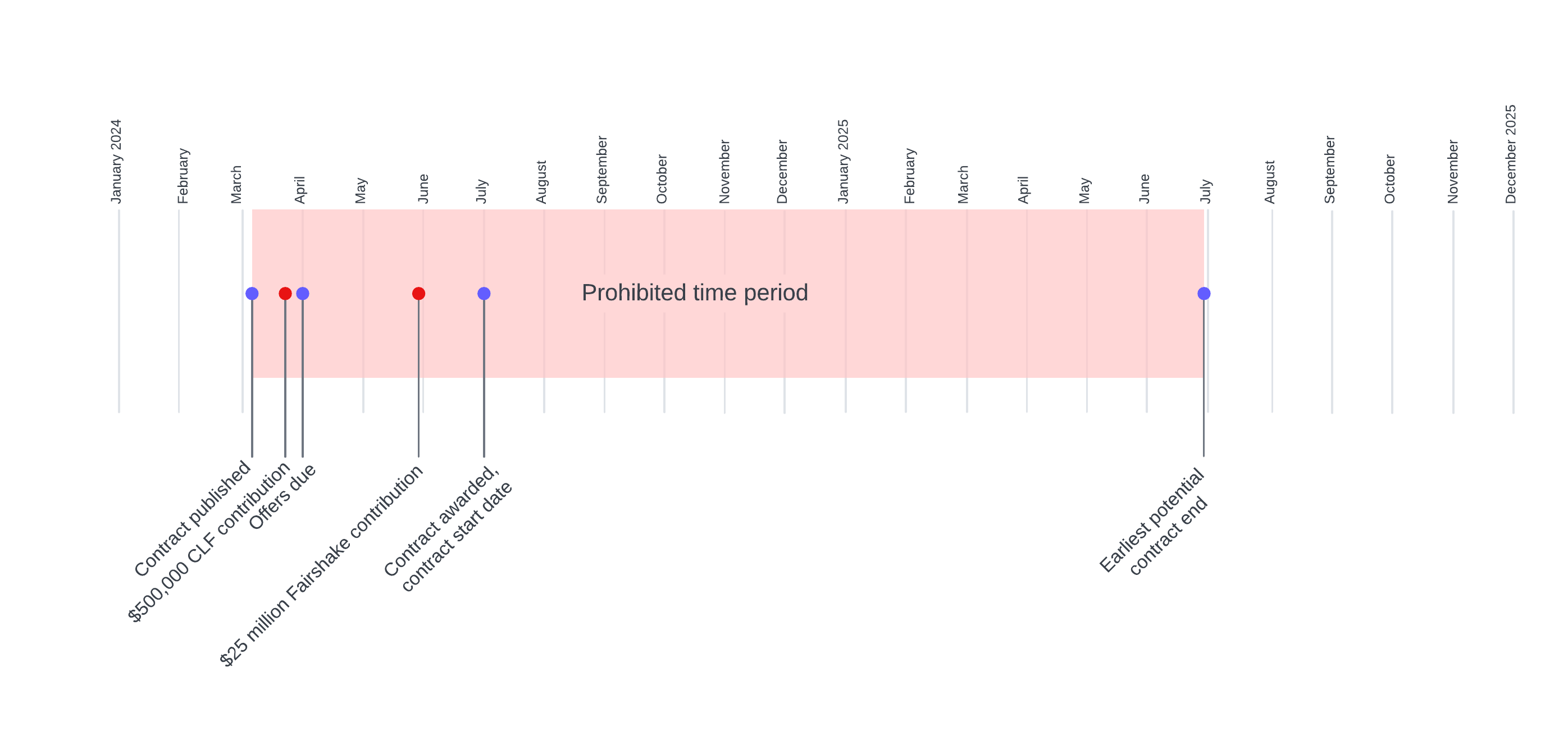

On March 4, 2024, the U.S. Marshals Service, an agency of the U.S. Department of Justice, published a contract opportunity for a provider to help them with “managing and disposing of large quantities of popular cryptocurrency assets”.4 The Marshals Service is in charge of holding cryptocurrency assets that have been seized as a result of law enforcement activity — including at least 164,000 bitcoins,5 with an estimated market price of around $10 billionb — and the Marshals periodically sell these assets once litigation has concluded.

Bids for the Marshals Service contract were due on April 1, 2024. On July 1, 2024, the $32.5 million6 contract was awarded to Coinbase,7 and Coinbase published a blog post promoting its selection for the federal contract the same day. According to the government website, the contract began on July 1, 2024 and will end on June 30, 2025 at the earliest.7

Campaign finance law prohibits federal government contractors from making contributions, or promising to make contributions, to political entities including super PACs like Fairshake. According to the FEC website, which is paraphrasing 52 U.S. Code § 30119 and 11 C.F.R. § 115.1(b), “The prohibition begins when the request for proposals are sent out or the negotiations have begun (whichever is earlier) and ends when performance under a contract is completed or negotiations have terminated (whichever is later).” This prohibition, and similar such anti-corruption laws, are often called “pay-to-play” laws.

With a request for proposals issued on March 4, 2024 and a contract that will end no sooner than June 30, 2025, the $25 million contribution on May 30, 2024 by Coinbase to the Fairshake super PAC is well within the prohibited time period. Another Coinbase contribution of $500,000 on March 20, 2024 to the Congressional Leadership Fund (the committee supporting House Republicans) also falls within the prohibited time frame.

After reviewing Coinbase’s contributions and government contract, campaign finance expert and Public Citizenc government affairs lobbyist Dr. Craig Holman confirmed, “It is illegal for a federal contractor to make a campaign contribution to any federal committee, including a super PAC. It is appropriate to file a complaint with the FEC.”

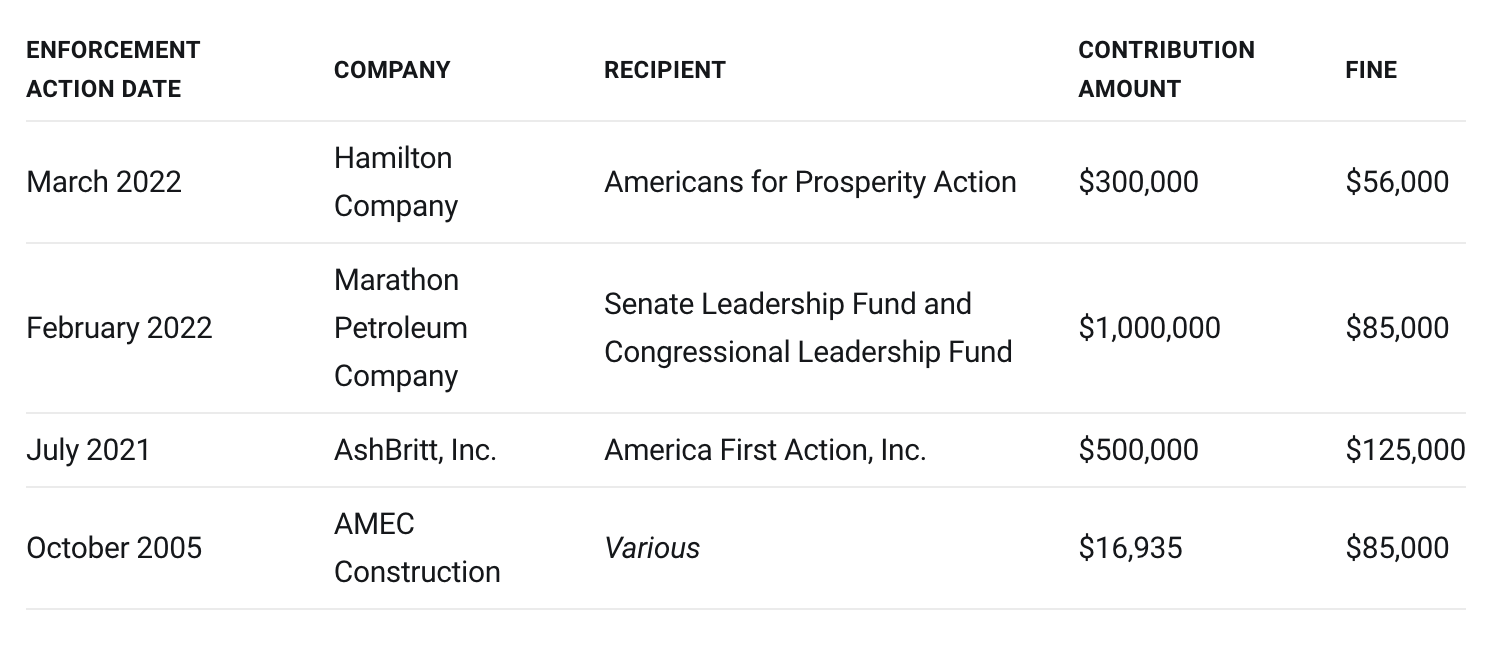

Historical cases

The largest illegal campaign contribution from a federal contractor to date appears to have been $1 million in 2022, contributed by the Marathon Petroleum Company to the respective super PACs for both House and Senate Republicans — one of which is the very same Congressional Leadership Fund that received Coinbase’s $500,000 donation. At the time, a unit of the Marathon company was in negotiations for a small, one-off contract to provide jet fuel to a government agency. Marathon’s lawyers claimed that the company had not historically engaged in federal contracting, and that they were unaware that the company was negotiating a federal contract at the time of the contributions. The violation resulted in an $85,000 fine.

According to FEC data,8 fines have been levied against other federal contractors for similar illegal contributions, though none of those contributions have rivaled the $25.5 million amount in these contributions by Coinbase.

A 2022 analysis of FEC enforcement trends by the law firm Holland & Knight observed that civil penalties against corporations that violated federal contractor prohibitions tended to be closely correlated to the amount of the violation, typically ranging from 17–19% of the amount. They also observed, however, that many violators obtained at least partial refunds of their contributions, in many cases offsetting the penalties.9

A possible loophole

Holman noted that some corporations have sidestepped FEC restrictions on federal contractors by claiming that the campaign contribution came from one entity, while the government contract was awarded to another. This most notably occurred in the case of a $2.5 million contribution in 2012 by the Chevron oil company, also to the Congressional Leadership Fund. Holman, working with the advocacy group Public Citizen, filed a complaint in concert with several environmental advocacy groups. However, the FEC ultimately dismissed it after accepting the Chevron corporation’s argument that Chevron (the political donor) and Chevron USA (the government contractor) were separate entities — despite the companies sharing a CEO and mailing address, and despite Chevron USA being a wholly-owned subsidiary of Chevron.10 Holman criticized the FEC’s decision at the time as one “that could create a loophole a million dollars wide for other companies to exploit.”11 A later petition to the FEC to close the loophole resulted in a 3–3 deadlock.

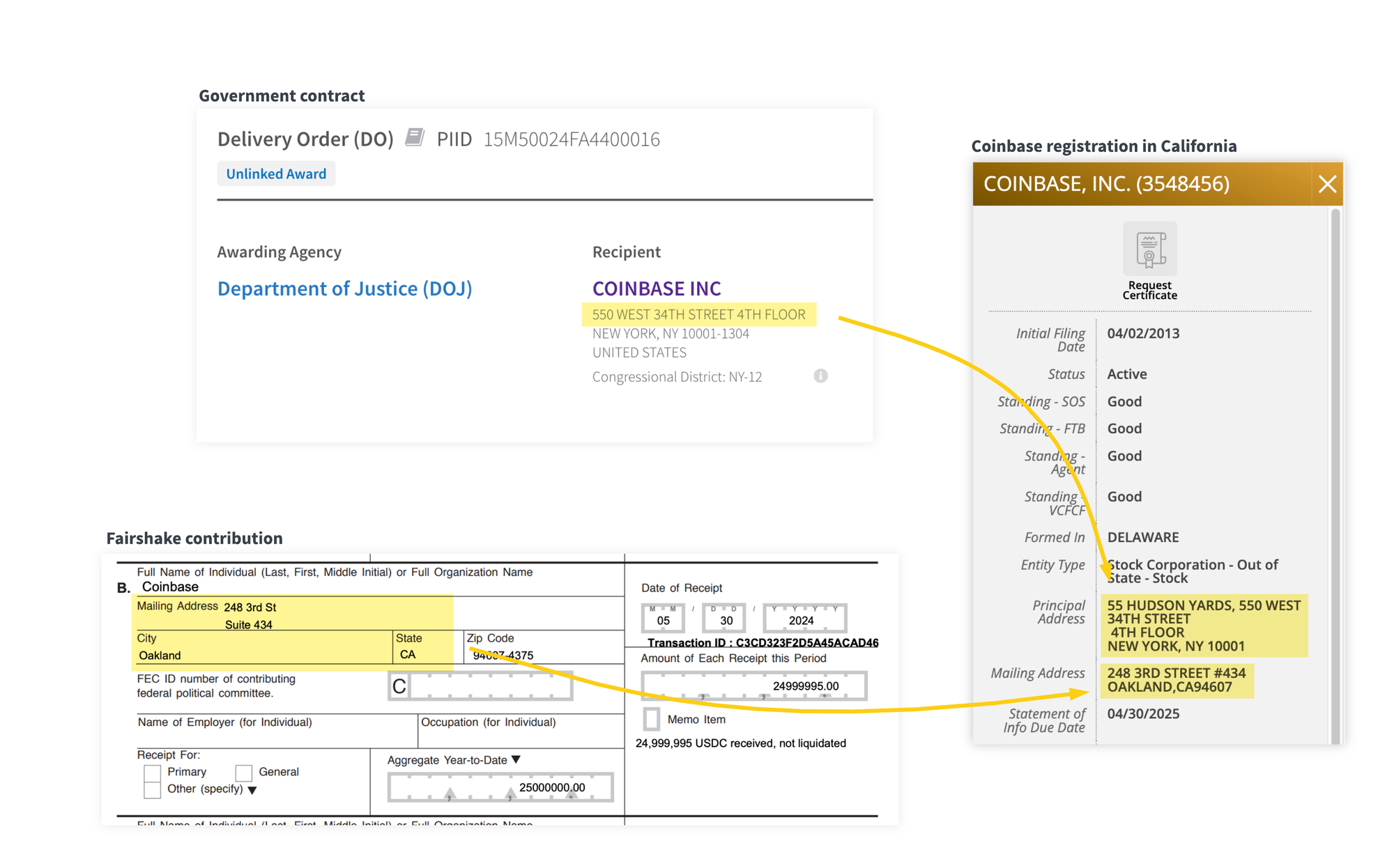

It’s not evident that Coinbase is trying to exploit this very loophole with this campaign contribution, but it is at least possible. The government contract and the campaign contribution are tied to “Coinbase Inc.” and simply “Coinbase”, with mailing addresses in New York and California, respectively. “FEC records are often quite general,” noted Holman, describing the difficulty this sometimes causes in establishing that a donor and a government contractor are the same entity. “It probably is the same, but I cannot confirm this with the data available.”

Coinbase claims to be “a decentralized company, with no headquarters”, suggesting that its business entities may not be closely tied to either particular location or mailing address.12 In multiple state records, Coinbase Inc. uses the same New York address as on the government contract as its registered address, and uses the same Oakland, California address as on the FEC contribution record as its mailing address.

Coinbase does have multiple subsidiaries, including one each registered in California and New York,13 although neither is mentioned by name in either the government contract or the FEC reporting. Various subsidiaries also use the same New York and California addresses as used on the government contract and FEC filings.

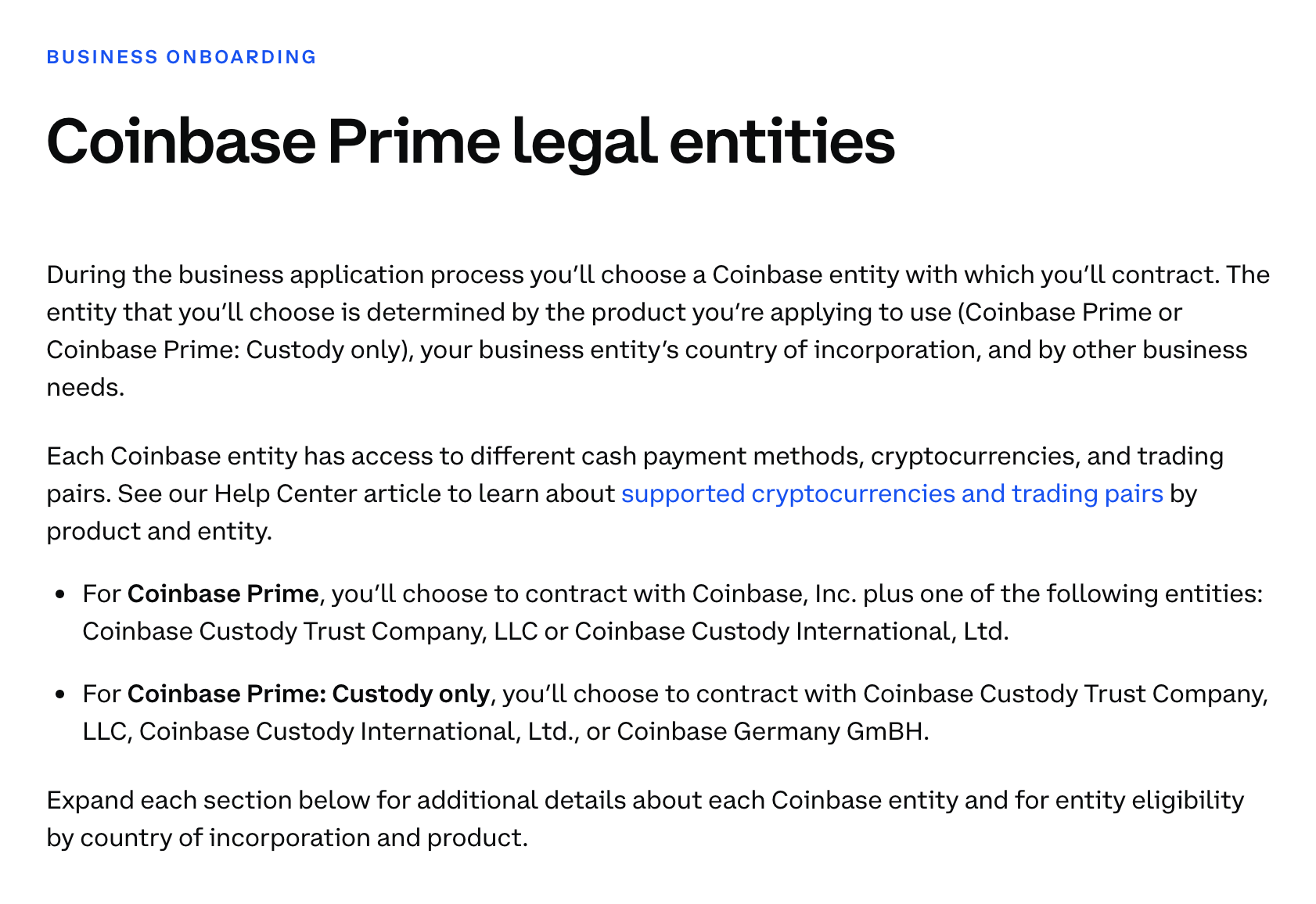

The New York subsidiary is the Coinbase Custody Trust Company, LLC, which shares the address used in the government contract, and it’s possible that this is an entity involved in the government contract. However, Coinbase’s own business onboarding documents for “Coinbase Prime” (Coinbase’s institutional service being used by the Marshals) explain that businesses that use Coinbase Prime will enter into contracts with Coinbase Inc. and either its local or international subsidiary (in this case, Coinbase Custody Trust Company). If Coinbase Custody Trust Company is indeed an entity involved with the government contract, despite not being mentioned by name, its parent Coinbase Inc. is likely also a party.

While Coinbase’s documents note that businesses do have the option to only contract with the Trust Company, and not with Coinbase Inc., this is for the “Custody only” solution, which does not include the institutional trading services that the Marshals have contracted from Coinbase.

A spokesperson for the Fairshake political action committee, reached on July 30, did not respond to requests for comment on the Coinbase entity that donated to the PAC, whether Fairshake had solicited the donation, or whether Fairshake had confirmed with Coinbase at the time of the donation their status as a federal contractor. The Fairshake website does note that federal contractors are prohibited from contributing to the super PAC (as does the website for the Congressional Leadership Fund).

Coinbase’s response

A Coinbase spokesperson, reached on July 30, declined to answer questions about which entities were associated with the government contract or the political contribution, or to respond to broader inquiries about the apparent campaign finance violation. They stated only that “Coinbase complies with all applicable laws, including campaign finance law.”

Two days after this article was published, Coinbase’s Chief Legal Officer, Paul Grewal, took to Twitter to argue that the company’s political contributions were not in violation of campaign finance laws. He further condemned this article as “misinformation”, which he insinuated may have been “intentional”.

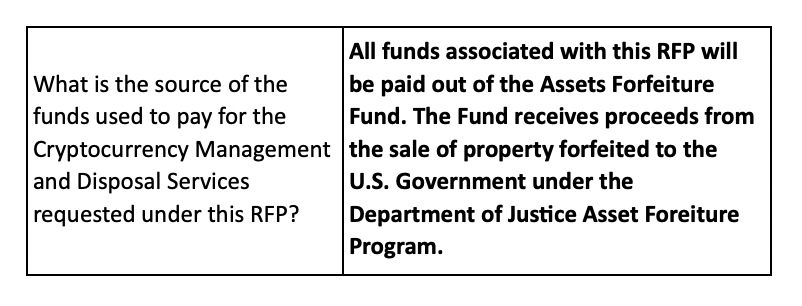

Grewal asserted that Coinbase is not a federal contractor, and thus is not subject to the prohibition, pointing to a definition of the term within the Code of Federal Regulations as those who are paid “in whole or in part from funds appropriated by the Congress”.14 He also pointed to a Q&A document that was published as an update to the request for proposals (RFP) on April 18, and which contains questions between (unidentified) prospective contractors and answers from the US Marshals Service. One such Q&A entry identifies the Department of Justice’s Assets Forfeiture Fund as the source of the funding for the contract ultimately awarded to Coinbase. “Coinbase is not a federal contractor under the plain language of 11 CFR 115.1. USMS isn’t paying us with appropriated funds—something it made clear in the public RFP,” Grewal concluded in his tweet.15

While this Q&A document seems to be what Grewal is drawing upon for his claim that the Marshals Service “made clear in the public RFP” that they would not be “paying [Coinbase] with appropriated funds,” there does not appear to be any statement within the RFP that explicitly addresses whether the funds for the contract are appropriated by Congress or not.

If Grewal’s explanation were to be accepted, it would be another massive loophole in laws intended to prevent the appearance of, or actual, corrupt “pay-to-play” behavior by federal contractors looking to secure multi-million dollar government contracts such as this one.

However, lawyers at Public Citizen weighed in: “Grewal’s argument that funds in the Assets Forfeiture Fund are not ‘appropriations’ is incorrect. Just this year, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a similar contention, making clear that an appropriation is simply ‘a law that authorizes expenditures from a specified source of public money for designated purposes’. Consistent with the Court’s holding, a report16 published by the Congressional Research Service explicitly describes the Department of Justice’s Asset Forfeiture Fund as appropriated by Congress.”

When met with that point, Grewal argued: “This isn't about the Constitution's Appropriations Clause or references to contractors that have nothing to do with political spending. It's about political spending by parties deemed to be government contractors by the rules that actually are relevant– 11 CFR 115.1, 28 USC 524(c)(1), etc. As the DOJ's Asset Forfeiture Management Staff has confirmed, AFF is ‘one of the leading non-appropriated sources of funding for federal law enforcement today.’d I'm sorry, but this is what a payment in seized crypto by USMS happens to be.”17 However, over the past five decades, both courts and the Department of Justice have considered the statutory creation of the AFF to be an appropriation.

The complaint

I have, with the help of Public Citizen, submitted a formal complaint to the Federal Election Commission. Because Grewal responded to the allegations only after the original complaint had been filed, we also filed a supplement to address his argument that Coinbase is not a federal contractor. You can view the text of the complaint on Public Citizen’s website, view Public Citizen’s press release, or read the full PDF versions submitted to the FEC:

- Complaint filed August 1, 2024

- Supplement to complaint, filed August 5, 2024

Next, the FEC will review the complaint to ensure it satisfies the criteria for a proper complaint. The Commission will then notify Coinbase and invite them to reply within fifteen days, after which they will vote on whether there is reason to believe a violation has occurred. If they find there is reason to believe a violation occurred, they will open an investigation or begin conciliation discussions with Coinbase.

An apparent campaign finance violation of historic size is not a good look for an industry attempting to regain legitimacy in the political sphere. Earlier overtures to politicians and regulators largely came from the cryptocurrency exchange FTX, whose CEO Sam Bankman-Fried had aimed to be “the adult in the room” representing the industry in policy discussions on Capitol Hill.

The collapse of his cryptocurrency exchange in November 2022, which revealed the massive fraud ongoing at the company, burned many of the bridges the industry had built with Congress, and embarrassed the many politicians who had accepted substantial donations from his company or illegally routed through its executives. Some political action committees that also received funds from FTX and Sam Bankman-Fried may have to forfeit some or all of the money illegally given to them.

Campaign finance violations played a role in the criminal case against FTX’s executives, and one executive convicted on a campaign finance charge, Ryan Salame, will be reporting to prison in the near future to begin his more than seven-year sentence. Ultimately, the case against Sam Bankman-Fried primarily focused on the financial fraud, and he was convicted and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

The harm to consumers as a result of the FTX collapse and the related disasters in the cryptocurrency world had seemed, for a time, to convince lawmakers of the need for stronger consumer protections in the fraud-ridden cryptocurrency industry. Those memories, unfortunately, seem to be growing ever more distant for some politicians as the industry is waving nearly $200 million under their noses.

Updated on July 31 with comment from Dr. Craig Holman, to add information about an additional possibly prohibited donation by Coinbase to the Congressional Leadership Fund, and with more information about Coinbase’s business addresses.

Updated on August 2 with comment from Paul Grewal, Chief Legal Officer at Coinbase, and further analysis based on his comments.

Updated on August 5 with the FEC complaint.

Footnotes

Eagle-eyed observers might notice that FEC data also show that Fairshake appears to have made a $25 million disbursement back to Coinbase on the same day of the contribution, which initially made me wonder if the PAC had returned the donation. However, this is just an oddity with how cryptocurrency-denominated contributions are reflected in FEC data, as I’ve noted in the past. Although Coinbase’s press team did not respond to an inquiry about this contribution, I was able to confirm with a Fairshake spokesperson that the contribution was not returned. Also, as I’ve noted, Coinbase announced the contribution several days later on their own blog. ↩

The dollar price is estimated solely from the current market price of bitcoin, but it’s worth noting that it would not be possible to sell such a substantial amount of bitcoins without impacting the market price. ↩

Public Citizen later joined me in filing a complaint to the FEC. ↩

Grewal appears to be quoting from a September 2013 issue of the United States Attorneys’ Bulletin. ↩

References

Schedule A form for Fairshake, Image #202401319618984579. ↩

Schedule A form for Fairshake, Image #202401319618984580. ↩

Schedule A form for Fairshake, Image #202406209652010582. ↩

Contract Opportunity: Cryptocurrency Managed Services - Class 1, SAM.gov. ↩

U.S. Government Bitcoin Holdings, 21.co dashboard on Dune. ↩

Cryptocurrency Managed Services - Class 1 Award Notice, SAM.gov. ↩

Contract to Coinbase Inc., ID 15M50024FA4400016, USASpending.gov. ↩

“Selected Cases in which the Civil Penalties are $50,000 or Greater Made Public Between 1980 and Present”, Federal Election Commission. ↩

“FEC Enforcement Trends: Federal Contractors in the Crosshairs”, Holland & Knight. ↩

Federal Election Commission Factual and Legal Analysis, MUR 6726. March 2014. ↩

“Critics Say Chevron Flouted Pay-to-Play Law. FEC Says It’s All Good.”, Mother Jones. ↩

“Coinbase is a decentralized company, with no headquarters”, Coinbase blog. ↩

“Coinbase Global, Inc.”, Fintel. ↩

Tweet thread by Paul Grewal. ↩

“Crime and Forfeiture”, Congressional Research Service, pp. 23–25. ↩